…Brisk April morning. Roughly zero dark thirty. Troops had been waiting forever, but the brass had insured “hurry up and wait” by trying to micro-manage an evolution that they had never seen fit to practice before.

They were late getting all the men into the boats and underway. It would be long after dawn before they arrived where the arms cache was reportedly hidden.

The men had been ordered to prepare their uniforms as if for a parade. A cruel waste of time. Almost none of the boats could access solid ground and most of the troops had to wade ashore through waist deep muck. So their uniforms parade ready (from the waist up), the British soldiers started their march to Lexington and Concord.

Military uniforms (intended to be worn in combat) have most definitely not always been practical. The intent here is not to prepare an exhaustive history of combat uniforms (or their camouflage subset), but rather to examine high points (and low) along the way. Part One examines some aspects as military uniforms prior to 1917 (especially in the U.S.) became (for the most part) more practical. Weapons, equipment and tactics only mentioned in passing (with the exception of the British Rifle Brigade) and concentrating on combat branches… most especially the Infantry.

The British soldiers marching toward Lexington Green were dressed for the day’s show of force… exactly as they would be for any other day. To a potential recruit who was thinking of “taking the King’s shilling” the uniform may have looked just fine… but even routine upkeep would prove to be a never-ending task.

” Contemporary sources state that the common British soldier spent more than three hours preparing his uniform for “parade”. The order in which they prepared was: First, dress the hair. Stiff curls were worn falling alongside the face and a “pig tail” in the back. This was accomplished by using an ample amount of pomade, or the end of a tallow candle. Then they had to powder their hair white. The next step was to shine the three dozen brass buttons on their red coats. All white facings had to be whitened with pipe clay.

Their shoes had to shine like new. The last article of clothing to be put on was their gaiters, which were whitened with pipe clay and put on WET to insure they fit snug when dried. The cross belts and waist belt were all whitened. Bayonet scabbard, short sword scabbard (if one was carried) and the cartridge box were shined. And finally, the “Brown Bess” musket was polished until it gleamed. The brown color having long been rubbed off, the muskets often shined like stainless steel.”

-AmericanRevolution.org-

Further information regarding the standards of grooming and appearance of troops in both the British and Continental Regular Army: https://www.scribd.com/document/260315949/Soldier-Hygiene-Grooming-Laundry

European armies were not overly concerned with practicality, and certainly not with “camouflage.” Aside from being mesmerized with spectacle… generals wanted to see and recognize their troops from a good distance (though sometimes enemy units might inconveniently wear same color.) Bad enough you might have to send some of your men out foraging… certainly wouldn’t want them to no longer stand out if they decided to take “French leave…” In any event tactics and weapons of the day in major battles required at least battalion sized units shoulder to shoulder.

The “unfortunate” experience of Braddock in the wilderness in the French and Indian War suggested that the British needed at least some units with more “flexibility…” “Light Infantry”… that could operate in smaller size units and be trained (and trusted) to operate independently. Sometimes used as skirmishers.

The natural evolution of light infantry in the British forces led… in the Peninsula campaigns in Spain during the Napoleonic Wars to the deployment of the “Rifle regiments…” Not only would junior officers be allowed (even encouraged!) to use their own initiative… but NCOs, and to some extent… individual riflemen.

The men were clad in green uniforms. They used rifles… not muskets. While a rifle regiment could fight quite splendidly as such, it was more routinely used in smaller groups. Not just skirmishing, but recon and combat patrols in terrain not well suited to cavalry.

The rifles took longer to load, but were far more accurate… a veteran rifle regiment could manage 3 rounds a minute to the musket’s 4 rounds a minute in the hands of excellent line infantry. (French skirmishers used muskets and did poorly against British riflemen who were deployed as skirmishers.)

Physical fitness was paid more attention than in line regiments (often riflemen on rough ground or deployed at a run.) Marksmanship of course was prized. Line outfits until much later in the 19th Century had the command, “Ready, present, fire!” “Present…” not “aim.” A Baker rifle could reliably drop men at 200 yards in the hands of a trained riflemen. Exceptional marksmen could obtain amazing results at much longer ranges.

The rifle regiments proved to be a template for modern infantry that would not be fully realized until well into the 20th Century.

In 1798 the U.S. Marine Corps was reconstituted. As part of the uniform a new leather “stock” was issued once each year to each Marine enlisted man and company grade officer. Approximately 3.5″ wide with one or two buckles in the back. Propaganda said that it was to “…protect the men from sword cuts…” In reality it was a barbaric means of keeping the mens’ chins up. Used also by British Royal Marines and some British line regiments.

Horribly impractical for anything but formal occasions. ( British observer remarked soldiers appeared… “Like geese looking for rain…”) Stock made it nearly impossible to aim a musket or rifle and pretty much negated peripheral vision.

Wise commanders reserved use to formal parades and inspections and the like… and certainly did not commit their troops to battle wearing them (though some British line outfits infamously did…) The Marine Corps finally retired the filthy things in 1872. The name “Leatherneck” remained… the name being far easier to wear than the stock…

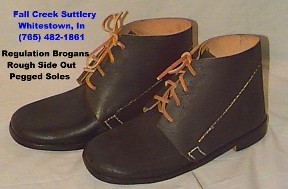

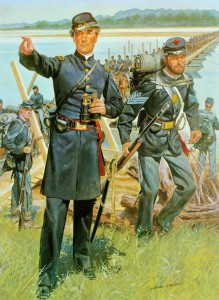

By 1846 at the start of the Mexican-American War, uniforms for Regulars in the U.S. Army had become far more practical. The Civil War updates for Union soldiers even more so. Still, there were issues. Leaving aside crooked contractors who (in the early part of the war) sold the Army shoes that would fall apart within a few miles and coats that would dissolve in the rain… there was still room for improvement.

Dark blue coats over sky blue trousers certainly better than British Red… but still a tad noticeable. The (decent quality) issue footwear for the infantry had no left or right shoes. While “lasts” to make both had been developed earlier in the century, they were not in common use. Infantry expected to alternate which shoe on which foot each day to “equalize wear…” Boots for officers were generally custom made.

Wool uniforms (by honest contractors) were durable, and kept heat in when damp. But often too light for really cold weather… and definitely too heavy for hot… and especially… humid weather.

While officers had fancy “cassock” type coats available, experienced ones who spent time in the field more likely to put their shoulder straps on a private’s four button “sack” coat. (Grant wearing one at Appomattox…)

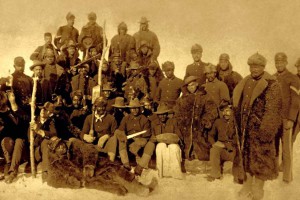

The Indian fighting Army after the Civil War started out wearing the same uniforms, but as the years passed more practical garb made available… and a great deal of flexibility on what was worn and how…

Looking at photos of regiments on the frontier, the black regiments seem to present a more military appearance. Part of that might be chalked up to their fierce pride (which led to a low desertion rate compared to white regiments…) But another reason was that their regiments were formed after the war. The last of the poorly made and worst fitting uniforms had already been issued and the black regiments got much better quality uniforms that didn’t fit like potato sacks…

https://gruntsandco.com/frontier-infantry-1866-91/

Winter in the South was colder than Union soldiers thought that it might be… but the Northern Plains might as well have been the Arctic in winter. Buffalo robes, hat… and sometimes “mitts” in order.

As the years passed, on campaign soldiers started to look more like cowboys or bandits. Near the end of the Apache wars American Infantry in company sized units marched across the Mexican desert often wearing only long underwear and straw hats during the day. Mules carried essential gear. The officers left their swords behind, made cold camps, and did without bugle calls until action was joined.

The troops that made these marches had no shirkers with them… no weaklings. With slight modifications their type could be seen on patrols in the Philippines, Haiti, and Nicaragua into the early 1930s.

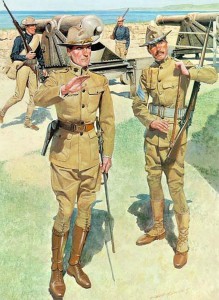

The Spanish American War saw most American soldiers deployed in blue wool uniforms, with some new features… a “campaign hat”, (worn by some but not all… some wore the light gray or brown model of earlier years…) leggings, and an early type of web belt first deployed in the 1870s.

The blue wool uniforms of course were not optimal for the campaigns in Cuba and the Philippines. Like many soldiers during the war the lad in the above photo has been issued an obsolescent black powder Trapdoor Springfield and will face Spaniards with modern Mauser rifles with smokeless powder.

https://gruntsandco.com/u-s-ordnance-rogue-fiefdom/

Shortly after the war with Spain, khaki trousers were issued… sometimes with a khaki jacket. The blue shirt continued to be worn for some years by soldiers and Marines with the khaki trousers. Both services would wear them for a time in the Philippines and in China during the Boxer Rebellion. The Army, and then the Marines would switch over to khaki shirts.

By the early 20th Century, Army and Marine Infantry had a (reasonably) durable field uniform that suited the climate of the Philippines and soon Latin America. The all khaki uniform was not highly visible. It was comfortable and easy to maintain. But come 1917 the uniform situation needed to be revisited.

Coming in Part 2, A Century of Change…

Suggested Reading: