The General sat at his desk and fumed. Thirty-five years in the Army and he was used to getting his way. But this damned “Second Land Army”, as he always insisted on calling it (except in public) was being more arrogant than usual.

He never saw any reason for it existing in the first place. Given his way he would gladly see it disbanded with its manpower and funding handed over to the Army. But he had to admit, they had come up with an excellent camouflage pattern. He wanted the Army to have it. But the arrogant bastards not only refused to share it… but had taken out a patent in an attempt to prevent the Army from having use of it!

He had thought to simply ignore that patent… this wasn’t the civilian business world and one military branch had no business using a civilian “technicality” to prevent a far larger service from having access to something that might well be useful in the field.

But in reading through the patent, he found that one of the names listed as patent holder was Heinrich Himmler. The Army would have to develop its own camouflage pattern. (From 1937 events…)

WWII German SS Camo Pattern Helmet Cover

World War One

In 1917 the Marine Corps offered to send two regiments of infantry to France aboard the first transports. While Pershing would welcome any trained and disciplined infantry that he could get, Stateside Army brass told the Marines that all transport would be tied up by the Army for many months to come. The Secretary of the Navy got around that by having the Navy rustle up its own transport and the Marines were among the first units landed.

The Corps had agreed to some changes in its regimental organization to match the Army’s structure. A pre-war Marine regiment was rarely formed and had component companies of only 100 men. It was barely equal to a WW1 Army battalion. So the companies were pumped up to 250 men and the battalions to a thousand.

The two regiments, (5th and 6th Marines) would be combined with two Army regiments (9th and 23rd Infantry) and form the 2nd Army Division. Each service unit would constitute a brigade within the division. With each brigade later getting a machine gun battalion, and an artillery formation… each individual brigade was almost as strong as a French or British division by that point in the war. The Commanding General of the division was from the Army.

The Army’s brigade contained many regular soldiers and was a good fit with the Marines. Together they would prove to be arguably the best division of the Allied Expeditionary Force…

But all was not roses. Many of the enlisted Marines might not have known that they were almost kept out of the war by being restricted from shipping. But they all knew that their superb Lewis machine guns had been confiscated from them as soon as they landed in France. For months they would have criminally inferior French castoffs.

They chalked that up against the Army…If not Pershing himself, then his staff. Actually it was Ordnance that was responsible. That organization would spend WW1 being slack, pig-headed, and rabidly insubordinate to Congress. The Army also suffered at their hands…the Army brigade getting stuck with garbage as well.

Ordnance forbade the brand new Browning Automatic Rifles from being sent to France (because the enemy might capture one and copy it…) Somehow the 79th Infantry Division went into combat with some in September 1918, but Ordnance immediately moved heaven and earth to confiscate them. See my previous story.

The Marines were wrong about Pershing. In many ways he was one of their best friends in France. His staff…not so much. Pershing himself could hardly be expected to routinely involve himself in most matters involving only two regiments in what would become a massive force.

Marine NCO 1918 (Naval Institute Press)

The Marines were told that they would have to surrender their uniforms and wear the Army’s “mustard-khaki…” The claim was that it would clutter up the resupply channels to have to provide for a different uniform requirement. The Navy gallantly offered to include replacement uniforms for the Marines…space available on warships that would dock in France.

The staff changed its tune and said that everybody would shoot at Marines because they would “look like Germans due to the greenish hue of their uniforms.” The Marines weren’t buying that since it wasn’t listed as a problem initially. The staff stood firm. They didn’t try to confiscate as originally envisioned…rather just waited for the trenches to rot the uniforms off the Marines’ backs. (As indeed happened over the months…meanwhile pretty much nobody shot at the Marines but the Germans.)

When the uniforms fell apart, the Marines cut their USMC buttons off the rags and sewed them on the Army replacement uniforms. The staff said that it was against regulations but the Brigade did it anyway. Until after Belleau Wood, enlisted Marines did not wear the Marine Corps Eagle, Globe and Anchor on the collars of their tunics… only officers. (Secretary of the Navy authorized for gallantry in that battle.)

As soon as the Marines hit France, the Army brass ordered U.S. Army type branch insignia (with Marine Corps emblems) to be manufactured, but those did not arrive until very late in the war, by which time the Marines were wearing the post-Belleau Wood authorized EGA’s on their collars. (See Army collar devices image below.)

Army issue Marine Corps collar insignia

A more severe blow to the Marine Brigade was the loss of their Commanding Officer. This time Pershing was responsible. He had Brigadier General Doyen sent back to the States and replaced him with an Army general… a personal favorite…his Chief of Staff who had gone from major to brigadier general in less than a year.

Though their officers kept them in line, the common Marines in the Brigade felt as motherless as hobos in a rail-yard. Two regiments of Marines. Famed historian S.L.A. Marshall described them as “…a tiny raft of sea-soldiers tossed about in a gigantic ocean of Army…” They felt as if they were going under.

But all was not as it seemed. Pershing was indeed responsible this time, but he was doing what he felt to be right. Pershing found that the Army was shipping high ranking officers to head up commands based on their seniority. Far too many were way too old for a field command. The oldest…his first duty upon reporting to his first post -in 1876- was to tell Mrs. Custer that her husband was dead.

Pershing demanded from the President…and got…authority to weed out the aged, ill, and infirm. General Doyen had been a fine Marine officer… but he was too old and infirm… Headquarters Marine Corps should never have assigned him… (Throughout the war the Marines would too often blame Pershing, when it was his staff… and the Army would too often blame the 4th Marine Brigade, when the offender was Headquarters Marine Corps…)

Marine Colonel Buck Neville, commanding the 5th Marines was next in line…and had been far senior to Pershing’s choice at the beginning of the war. He should…in the normal course of events…have been given the command. But events were not normal. Pershing knew that the 2nd Division would probably be the first in action and he had to be sure that it would meet the test…and he knew almost nothing of Neville.

Army Brigadier General James Harbord was nothing like Ned Almond (picked out of place by MacArthur whose favorite he was in 1950 to head 10th Corps). Harbord was tough, smart, and perceptive. He never told Pershing what he thought that he wanted to hear… He would give him the truth, with the bark on.

Pershing shook Harbord’s hand and firmly told him… “I’m giving you the finest infantry in France…I expect you to command accordingly.”

Neville was too good an officer to sulk. He determined to give his full support to the incoming general…but he also wanted to see where the new commander stood. He shook his hand…then handed him two Marine Corps emblems to put on his Army uniform.(1) This could be viewed as both a welcome and as a challenge… and indeed it was both.

Harbord wore the EGA’s during the time that he commanded the Brigade. He demanded the best, but the Marines responded not only to his superb leadership… but also as only men who are treated right by someone that they initially assumed to be an enemy can. He never let any staffer raise the issue of Marine buttons on Army uniforms or other such drek. He was their “Godfather…”

Harbord went on to briefly command the division…but Pershing needed him to untie the logistic nightmare that faced the AEF. (2) After some temporary commanders, Pershing placed the U.S. Army’s 2nd Division under the command of General John Lejeune, USMC in August of 1918…who would command until after the 2nd Division was relieved the following year from occupation duty in Germany.

Being attached to the Army in France had innumerable benefits for the Marine Corps that would pay major dividends in WW2. In addition to combat experience among many officers who would wear stars in the later war… many Marine officers had command experience not only with the Marines, but a fair number attached to staffs of Army divisions (though they had to wear spurs on such duty…) Heavy artillery use…and on a large scale.

The public image of the Corps had been massively enhanced (fairly and unfairly…the last not the doing of the Brigade, but of HQMC…) But some “identity issue” memories remained…again more with HQMC than with the Brigade.(3)

To this day the 5th and 6th Marine regiments proudly remember their being part of the U.S. Army’s 2nd Division. (See image below…)

Institutional Memory

WORLD WAR 2 and Korea

Prior to the U.S. involvement in WW2, the Army decided to look into the possibility of camouflage uniforms…and handed the project off to the Corps of Engineers.(?) Outside input was also requested.

American horticulturist Norvell Gillespie, the garden editor of magazines such as Sunset and Better Homes and Gardens, designed the jungle camouflage print used by the U.S. military in World War 2.

Essentially the material as used by the Army and the Marine Corps was the same, though differences in cut, pockets, etc. for each service. Early on a camouflage “overall” was made available. The Marines pretty much passed… The Army tried some in New Guniea and elsewhere. Sadly, in tropic locations dysentery fairly common and the overalls did not have a “trap door” and soon were discarded.

Two-piece camouflage uniforms did make it into the European theater. At least major parts of two divisions… the 2nd Infantry Division and the 2nd Armor were sent into France in 1944 wearing camouflage. (See images below…)

Normandy 9th Infantry Division (U.S. Army)

9th Armored Division, Normandy (U.S. Army)

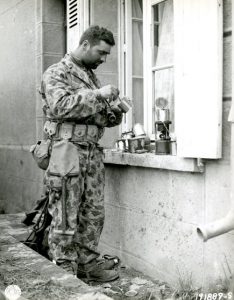

No evidence that camouflage helmet covers of the same material were ever issued to American troops in the European Theater. Either they were not sent or the brass decided not to issue them. Photos do exist of American soldiers in the ETO wearing camouflage covers on their helmets, but they seem to have all been constructed from material cut from camouflage parachutes. (See images.)

First Lt. George Kerchner, Ranger commander at Pointe de Hoc (U.S. Army)

Helmet cover made from camo parachute material

The Army had some of the same issues with the camouflage uniforms that the Marines had the year before in the Pacific. There was also a concern as to “friendly fire…” The soldiers landing in France had tangled with Waffen SS who wore camo uniforms, (and increasingly, German Army regular forces wearing their own pattern helmet covers, smocks, and ponchos.)

The camo uniforms in the ETO were withdrawn. Some would wind up as post-war surplus (being used by hunters…the pattern eventually being called “duck hunter”) or sent to French troops in Indochina.

The Marines in the Pacific started getting the two-piece uniforms in 1943. Marines wore them on Bogainville but the most complete issue was to the 2nd Marine Division in New Zealand, preparing for the invasion of Tarawa. Uniforms, helmet covers, E-Tool covers, shelter half… ponchos. (First issue camo helmet covers as used on Tarawa did not have the “slits” for inserting brush that later models did.)

Marine at Tarawa (USMC)

Tarawa proved the uniforms to be a failure. Did a great job of being reversible, but the fabric was far too heavy and did not “breathe” properly. Tarawa was 60 miles off the Equator… If the fabric became wet it stayed wet for a very long time. The sleeves were “tubular” and not designed to be rolled up.

The camouflage pattern itself proved to be a failure…at least for an entire uniform. The brownish “beach” side wasn’t too bad, though it had one major fault…(see below) but the mostly green side was a great design…for somebody hiding in the bushes…if they moved, it made them much more noticeable than if they were wearing a simple green fabric.

Both the brown and the green side shared another problem. The pattern was too small. For bird watching or hunting in place, not bad if blending in with matching vegetation. But, without getting technical… very close up, small patterns work… farther out they just look like a blob.

While some camo shirts worn by some 2nd Marine Division lads on Saipan, the Corps was through with the uniforms in that pattern for any mass issue. The helmet covers and shelter half retained until the early 1960s…the ponchos issued until no longer serviceable…mostly by the early 1950s.

Other than the Alamo Scouts in MacArthur’s command, most soldiers in the Pacific either were never issued camo uniforms and helmet covers… or stopped wearing them well before the end of the war.

But HQMC noticed something about the camo helmet covers. Civilians watching newsreels soon came to identify camouflage helmet covers with Marines. Too many times earlier in the war, Marines with bare “steel pots” had been identified as “soldiers” in newsreels. HQMC made a mental note.

Immediately after the surrender of Japan and the occupation by American troops, MacArthur’s staff ordered a giant parade (one of countless film opportunities for General MacArthur.) Appended to the order for the various commands was a note that the Marines were not to wear their camouflage helmet covers.

Many Marines (and HQMC) felt that this was a slight… that they were to be denied recognition in the newsreel that would be made. Some blamed MacArthur. No way of knowing what was the thought behind the order. Maybe some anal staffer simply wanted all helmets to look alike.

Doubtful that MacArthur involved at all. While he loathed Marines at the start of WW2, he deeply respected them by the end, and early in the Korean War threatened to resign if the Pentagon did not send him the First Marine Division to launch his invasion of Inchon.

Korean War

Before the Korean War the Army decided to see about coming up with a new pattern of camouflage for helmet covers. A design was approved, but a contract was not issued.

When the Korean War broke out the Marines rushed one regiment, some supporting arms (total labeled 1st Marine Brigade) and some air support. Somewhere over the years, the Marines in this regiment had not kept camouflage helmet covers as routine inventory. Most of the Marines in the “Fire Brigade” in the Pusan area had bare helmets. Newsreels again often referring to them as “soldiers…” And again, HQMC took note.

When the Brigade joined up with fresh units to become the 1st Marine Division, the Corps saw to it that camo helmet covers were available and worn by all. Never again would a Marine unit deploy without them. I have seen photos of some Marines in Korea in the last 18 months of the war wearing WW2 pattern camo shirts… They were part of a local “recon” team. Interestingly they wore the shirts over their body armor.

The Army requested that a production run be made on “their” helmet cover design…(having by this point left the previous design to the Marines.) A production run was made and space on an old freighter hauling other supplies was found. Unfortunately the ship sank in the North Pacific. The Army got another run…but only in the last weeks of the war. (See image of probable pattern below)

Army developed camouflage helmet cover (Author paid image licensed by Canstock.)

Whatever the Army brass was doing, company grade officers in the field decided to take matters into their own hands. Fabric helmet covers had been used as far back as WWI by the Germans…mostly improvised…and the U.S. Army was going to do the same in Korea.

Aside from any camouflage patterns, fabric covers “softened” the silhouette a bit at distance… eliminated any glare from bare metal, and mostly eliminated any metal sound if helmet hit branches, etc. So by 1951 various materials being used…sandbags, combat fatigue cloth, etc. (See image below.)

Joe Clemons, C.O. King Company, Pork Chop Hill, 1953 (U.S. Army)

Post Korea – Pre Vietnam – Vietnam

The Army and the Marine Corps returned from Korea with a renewed interest in camouflage uniforms. The Marine Corps still had stocks of WWII two-piece camo. Some experimenting in the field… but the problems remained. Eventually remaining stocks issued to Recon.

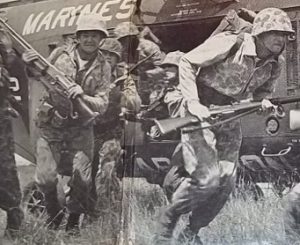

Marines exiting chopper 1960… (USMC)

The Army in Germany in the 1950s had access to Wehrmacht WW2 camo stocks. Various experiments carried out. Some of the troops flown into Lebanon in 1958 were wearing various types of camo from the experiments.

American soldiers experimenting with German camo (U.S. Army)

Meanwhile, the Marine Corps had introduced a new, Marine Corps specific, utility (combat fatigues) uniform. A definite improvement over the many variations of combat fatigues used in Korea. The uniform was handsome yet simple. Flaps covered and protected all buttons (except the very top which was normally not closed.) The material was durable and (pending any adoption of camouflage) seemed to meet their needs for coming decades.

U.S. Marine 1st Lt. wearing pre-common service issue utilities (USMC)

One potential problem. The uniform “blouse” was too heavy of a fabric for sustained use in the tropics. This was made worse by a very large inside pocket on the wearer’s left side. A “map pouch” that doubled the thickness of the material.

There *was* consideration of a “new” camouflage uniform. This would be in a “broad-leaf” pattern using larger pattern to avoid the problem with “duck hunter…” The pattern actually was a 1948 design that got shelved.

Summer Leaf pattern test

The Corps considered it…and some test uniforms (including field jackets) were produced. Absolutely gorgeous… but “gorgeous” is not a field requirement. Reversible…would look splendid in New England forests.

But too many problems. Reversible pattern increased weight of fabric. The uniforms were cut exactly like the new Marine Corps utilities… right down to the map pocket. While some were produced in Asia for Americans in Vietnam in the early 1960s… the uniforms themselves were “no-go…” However, a variation of the pattern would make its way onto helmet covers and shelter half prior to the Vietnam war and would be the pattern for decades.

Robert McNamara and the bean counters arrived. Tradition and pride meant nothing. The same people who would send individual replacements to Vietnam like so many spare parts… had no patience with “individual service expression…” The services had “standardization” rammed down their throats. Same boots for everybody…same combat fatigues. They *graciously* allowed the services to keep their own fatigue caps, belts, and buckles.

Jointly procured combat fatigue shirt

The Army didn’t like it much and the Marine Corps even less. Their elegant utilities could no longer be produced. So too with their classic camo helmet covers and shelter half. Wasn’t the Army’s fault, but the Corps, in the field… was going to look a lot like “more Army…” To make it worse…the damn uniforms were no good for the tropics.

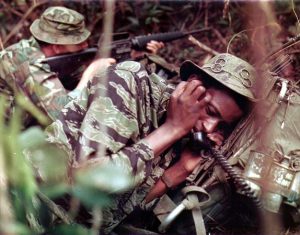

In Vietnam both services would wear the well-designed jungle fatigues. (See Part II of this series.) But both services also experimented with camouflage uniforms. Mostly recon teams…locally produced tiger stripe uniforms… then American camo version of the jungle fatigues.

Recon team RVN… (U.S. Army)

U.S.M.C. Vietnam era jungle uniform in Army developed ERDL camo pattern

The Marine Corps really into this latest pattern and design. Eyes on adopting it as their standard issue when they returned from Vietnam. But that was not to be.

Rhodesia

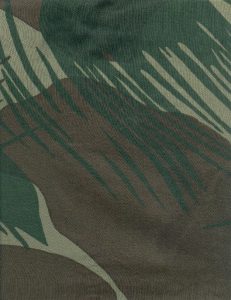

Meanwhile in Southern Africa in the mid 1960s the Rhodesian government was looking for a camo pattern to be issued to all services in its slowly escalating bush war. Some of their senior officers had served in the Long Range Desert Group in North Africa, and the SAS there and in Malaya. One pattern was quickly agreed upon.

Rhodesian Security Forces camouflage pattern

Close up you could see both small patterns and large…the smaller to help a soldier who might be concealed in the bush… At a distance only the larger patterns visible. (See photo below… Yankee Papa image 1976)

Rhodesia, field briefing (Image by Yankee Papa)

The Rhodesians had the advantage that their uniform only had to be appropriate to one area of operations. A field jacket in the pattern was issued since in the High Veldt in winter, frost could frequently be encountered in the morning. The only real flaw was the buttons… too small, too weak, and sewn on with cotton thread. The lads replaced with larger, tougher buttons in the same color with nylon thread.

Post-Vietnam

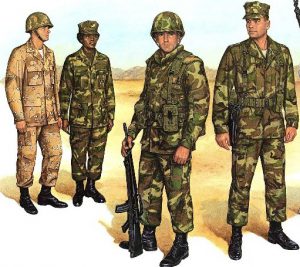

The Marine Corps hopes for adopting the Vietnam jungle uniform as the template for their future utility uniform crashed on the rocks of standardization. It is said that “…an elephant is a mouse designed by a committee…” The “Woodland pattern BDU” wasn’t that bad… but it was a “compromise…”

The Corps wanted to keep the upper slash pockets (goes back to old paratrooper design to allow easier access when wearing web gear…) That was rejected… straight pockets would be the standard. The size of the pattern would be adjusted, colors flattened. It was what it was and both services would have to live with it for the next two decades.

Rather than rip-stop cotton, it would be a 50-50 nylon/cotton. Both the pattern and the weight geared to Northern Europe. Overheating of troops led to the Army and the Marine Corps issuing their own lightweight rip-stop blends. In spite of being specifically designed *not* to be starched… commanders could not restrain themselves and in many commands starching became mandatory.

Marine BDU images 1980s (USMC)

Gulf Wars

In Gulf War One the Army and the Marine Corps were issued a desert specific uniform in what the troops called a “chocolate chip” pattern. It was handsome enough looking, but the issue of the “small pattern” was raised again.

At the start of Gulf War two the standard desert uniform was essentially tan with very large markings scattered upon it. Neither service particularly fond of it.

MARPAT

The Marine Corps decided to “go rogue” (so to speak) and design its own battle dress utilities. While this was not done in secret, it was well below many radars. The Corps wanted regular and desert patterns. They commissioned scientific research and managed to achieve what they were looking for at a remarkably low cost…(in view of what would follow… amazingly low…)

Marine MARPAT BDUs (USMC)

The Corps knew that it had a world beater. It also had a camo pattern all its own. It expected other services to attempt to “co-opt” the pattern. Not just service identity… but imagined images of National Guardsmen in wrinkled BDUs that hung like pajamas walking around shopping centers in the new pattern. (Marine Reservists essentially not allowed to be in public…other than driving to drill…in camos while not on official tasks.)

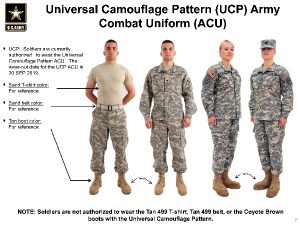

A patent was obtained. The “MARPAT” was no longer under the radar. The Army (with some justification) wanted to know why, if MARPAT was the best available, they couldn’t have it too. Certainly, if the Corps had a new (and best) anti-tank rocket, the best out there, they couldn’t put a patent on it to keep the Army from having the rockets as well.

What happened next is a puzzlement. One would have expected the Secretary of the Army to go to the Secretary of Defense…and a “stand and deliver” order be given to the Marine Corps. But it didn’t happen that way.

It might have been that while the Army had a burr under its saddle… They made the complaint…but saw this as a golden opportunity to design their own all-Army uniform… and come up with a better product than the Marines had.

UCP – ACU

The Army brass, somehow… in spite of spending vastly more money than the Corps had came up with a camouflage pattern that was an embarrassing failure. How did it happen? Were combat troops not consulted?… Didn’t *anybody* with veto power take a good long look at it? The pattern and color scheme might have been a winner…at the battle of Stalingrad.

Back to the drawing board (U.S. Army)

The Army took more care to come up with a decent replacement pattern… The replacement candidates certainly better thought out.

Meanwhile, the Marine Corps has stopped issuing the desert pattern MARPAT as a Summer Stateside uniform. It is restricted to Marines assigned to overseas desert environments. The “Winter” combat uniform is now to be worn all year round in the United States. In warmer months the sleeves authorized to be rolled up.

As a final note. The Woodland BDU’s are not missed…if for no other reason than the fact that the color/pattern in use by a number of armies that we may have to fight… including some Red Chinese formations.

-Yankee Papa-

COMING IN PART IV…THE FUTURE – NOTHING CAN GO WRONG…GO WRONG

NOTES

(1) Marine officers not in France…especially those at HQMC made some disparaging remarks about Harbord being given the Marine collar EGA’s. Mutterings of “buttering up the new boss” were heard. The Marines at the “sharp end” with the 4th Marine Brigade knew better…as did Harbord.

(2) After the war, President Wilson sent Harbord on a fact-finding mission to the Mideast. He supported the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. Harbord reported on massacres of Armenians by Turks, collected information about them and was an eyewitness to at least one. He retired from the Army in 1922 and became the head of RCA until 1947.

(3) The gripes between the Army and the Marine Corps…especially re WW1 are nearly endless…and all too often misdirected or in error. I have gladly ignored almost all of them except those directly pertaining to this article. Otherwise, to paraphrase Gandalf in Lord of the Rings: “If all the grievances standing between the Army and the Marines are to be brought up here… then we may as well abandon this article…”

(Xtra) Complex guide to camo

SUGGESTED READING