American Infantrymen have had nicknames since the nation’s founding. Traditionally, they have almost always had their roots in derisive comments by our enemies or even fellow branches that have looked down on the “Queen of Battle”. That term in itself seems insulting unless one is aware the Queen is actually the most powerful piece on the chessboard able to go anywhere and in any direction just like the Infantry on the battlefield. Time and again on our battlefields, history has seen the Infantry’s accomplishments and unmatched sacrifice turn epithets into honored noms de guerre desired by many and adopted by some.

“Yankee Doodle” was among the first coined from a song of the same name. British troops used it to mock colonial soldiers. Doodle is supposedly derived from the German “dudel” for fool or simpleton. The term came to be one of pride by the early colonials as a rag tag army resisted the best army in the world and after eight years earned our nation’s freedom. For much of our history and outside the US, “Yankee” has been a term not just descriptive of Infantrymen but all Americans, a phenomenon that would be repeated again and again.

Historically, the next most popular term came to be “Billy Yank” & “Johnny Reb”, referring to the combatants of the North and South respectively during the Civil War. The nicknames source is pretty straightforward considering the common names and struggle between the “Yankee” North and Rebellious South.

“Buffalo Soldiers” became a term of use for the black soldiers of the 10th Cavalry during our frontier days. Some say it was coined from the similarity to the soldier’s hair, others for their courage and others for the common use of buffalo coats by the troopers. In any case, “Buffalo Soldiers” became a term of honor.

During World War I “Yank”, short for Yankee, became a common term popular well into WWII and after but the period is defined by the nickname “Doughboy”. “Doughboy” actually tracks back to the Mexican American War of 1846. It most likely originated from the appearance of American Infantry after long road marches on primitive roads. Dust would cover the troops giving them the look of unbaked dough. Later in WWI some surmised the term was one of derision by British troops because of American troops’ lack of experience. Belleau Wood, the Marne, Amiens and Meuse-Argonne clearly demonstrated America’s expertise in the profession of arms and especially the pluck of American Infantry. “Doughboy” came to be applied to all soldiers and even the few Marines to fight in WWI to their dissatisfaction.

World War II saw the widespread use of “G.I. Joe”, often shortened to “G.I.”. “G.I.”, short for General Issue, is a military logistics term applied to many of the sundry items generally issued each soldier. As with the ubiquitous nature of general issue items, so the nickname was applied to most American uniformed troops to include the other branches.

Infantrymen on the other hand have throughout time had the ignominious honor of being compared to various animals, few as memorable as the term “Dogface”. “Dogface” as an infantry nickname came into popular use in World War II. Its derivation could be from the identification tags worn by all soldiers that were commonly referred to as “dog tags”, but Phillip Leveque who served in the 354th Infantry put it this way:

“Perhaps I should explain the derivation of the term “dogface”. He lived in “pup tents” and foxholes. We were treated like dogs in training. We had dog tags for identification. The basic story is that wounded soldiers in the Civil War had tags tied to them with string indicating the nature of their wounds. The tags were like those put on a pet dog or horse, but I can’t imagine anybody living in a horse tent or being called a horseface. Correctly speaking, only Infantrymen are called dogfaces. Much of the time we were filthy, cold and wet as a duck hunting dog and we were ordered around sternly and loudly like a half-trained dog.”

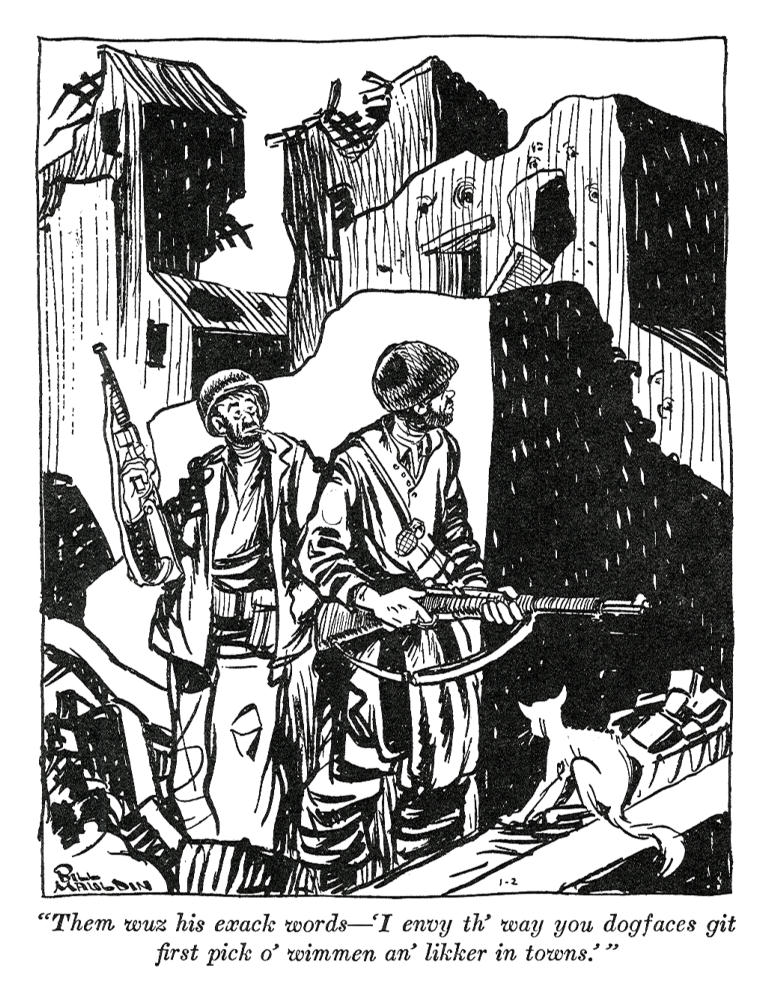

“Dogface” owes a lot of its popularity to Bill Mauldin’s cartoon characters Willie & Joe who epitomized the day to day existence of the Infantryman in WWII. His cartoons are classic.

“The Dogface Soldier”, written in 1942 by Cpl. Bert Gold and Lt. Ken Hart, was adopted by Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott Commander of the Third Infantry Division and remains that division’s song today. It sold 300k copies in 1955. It was popularized in the movie “To Hell and Back”, the biography of Medal of Honor awardee Audie Murphy who played the title role. Audie Murphy, the most decorated soldier of WWII, served in the 3rd ID. Its lyrics are an uncharacteristic, not often publicly stated testament of the Army Infantryman’s fierce pride.

Since WWII a variety of Infantryman nicknames have been born. Groundpounder, Crunchy, 11 Bang-Bang, 11 Boom-Boom, 11 Bush (the Army and Marines denote Infantrymen with a variety of numerical codes that include the number 11), Knuckle Draggers and Earthpig, but none are as well-known and have become so ubiquitous as “Grunt”.

It should be noted, Marine Infantry nickname history has mostly differed from Army Infantry history to this point except for the short use of “Doughboy” in WWI. Marines have a long tradition of being Marines and rifleman first though there are great practical differences in being a rifleman and being an Infantryman. It was during and after WWII that Marines started developing other specialties in support of the Infantry. For example in WWII the Marines relied on the Army for artillery and armor support.

The lineage of “Grunt” is difficult to ascertain. Some associate the term with the sound a human makes when shouldering a heavy burden. Others associate it with the term “grunt work” coined in the early 1900’s and often referring to physically demanding, difficult but not mentally challenging menial work.

One of the most likely explanations comes from the shortage of Infantrymen in WWII where the shortage in Europe was by far the most acute. All infantry units in WWII at one point or another suffered troop shortages and in the heat of battle impressed troops who were not trained Infantrymen into the front line. Nowhere was it as bad as in Europe, where some infantry divisions suffered almost 200% casualties over the course of the war. Infantrymen made up about 5000 of a 15000 man division. They typically endured 90% of all casualties. Non-infantry soldiers from rear echelon units, as well as artillery and especially air defense soldiers were permanently reclassified as Infantrymen and pressed into the line. Some would undergo short in-theatre training. Many soldiers did not and often arrived at the front line never before having fired an M1 rifle.

These troops were categorized as General, Replacement, UNTrained, the likely birth of the term, “Grunt”. I could find no documentation of a “Grunt” stamp or even the use of the word during WWII but the term slowly came into use with its heyday coming with Vietnam.

Major H.G. Duncan USMC best communicated the spirit of the term “Grunt”, “Term of affection used to denote that filthy, sweaty, dirt-encrusted, footsore, camouflage-painted, tired, sleepy beautiful little son of a bitch who has kept the wolf away from the door for over two hundred years.” “Grunt” has been in popular use since, but like many previous Infantryman sobriquets, some have bastardized it to describe many more than the Infantryman.

Personally, “Dogface” is my favorite Infantryman’s nickname. Dogs come in all shapes and colors. They are often mistreated, unwelcome in finer company or generally thought poorly of. They aren’t the cleanest of animals, often have annoying habits and tend to make a mess. Despite all those flaws they possess a quiet honor. They are fierce in their owner’s defense, bottomless in their love and live to serve. Truly, they are man’s best friend as the Infantryman is for every American.