Marines landing Lebanon 1958. Photo USSCapricornus.homestead.com

Marines landing Lebanon 1958. Photo USSCapricornus.homestead.com It has been said by many that the United States has not launched an amphibious assault since Inchon in 1950. The 51 Marines and Navy Corpsmen killed and 203 wounded in Operation Starlite in Vietnam in 1965 (and four times that number of VC) might disagree.

Still, the operation was quite a bit smaller than Inchon… and while there would be other assaults from the sea, the Vietnamese enemy never let themselves be caught flat-footed like that again.

A Marine division was poised to land in Kuwait (while two others were on the ground). But they did not land. Their mere presence tied down many of Saddam’s troops, while the rest of the Allied force either broke through his defenses elsewhere, or swung wide.

Since the subject here is American amphibious capability, I will only mention the “moon shot” effort of the British in the Falklands. (For now, they no longer have that capability.)

But if one is talking an actual strategic large scale amphibious combat landing into enemy fire… then yes, Inchon was it. Of course the United States hasn’t set off a nuclear weapon in anger since 1945… but has improved and increased its stores of such weapons (and their offshoots) quite impressively since then.

For numerous reasons, the United States requires a serious amphibious capability. It is an incredibly complicated capability and is almost uniquely an American form of warfare. The Marine Corps, supported by the Navy provides that capability. It was not always so.

When it comes to my beloved Marine Corps, there is Marine Corps history… and there is Marine Corps propaganda. The history is impressive enough… the propaganda too often “fills in the cracks…” So too here, the Marine Corps for much of its history was not a major player in amphibious warfare.

American Marines had of course gone ashore (often with “bluejackets”) to take part in “punitive actions” and other operations requiring bayonets on the ground… but few of their actions were anything resembling modern amphibious warfare. The one major American amphibious operation prior to the Civil War was the landing at Vera Cruz during the Mexican War… only a handful landed were Marines… the rest being soldiers.

By the 1870s the Marine Corps was in the doldrums. Its senior officers were aging and its missions were vanishing. The Navy’s age of sail closing down… No more Marines in the riggings. A “mutiny from the ranks” by sailors on a Navy ship pretty much unthinkable for well over a generation.

The quality of Marine Corps officers varied wildly. Some were outstanding, but too many were indifferent at best. The Marine Corps had been forced by politicos to accept new lieutenants from dubious sources for direct commissions.

Some were dropouts from the Army and Navy academies… (sometimes made good officers, even if they failed calculus, sometimes not… drunk on duty, etc…) The worst were usually direct commissions from civilian life pushed upon the Corps by SECNAVs acting on behalf of various administrations keeping politicians happy.

Increasing numbers of Navy ship captains did not want Marine detachments on their ships (while detachment officers answered to captain, there were limits as to his use of the Marines.) The Marine Corps was about to be swept onto a lee shore.

A lot of Navy officers decided to take a measure that would lead to the eventual fading of the Marine Corps into irrelevance and eventually extinction. They petitioned SECNAV to commission no more Marine officers and just have Navy officers put over the enlisted Marines.

Problem with that was that each SECNAV understood what some admirals did not (even into the mid 1950s). The Marine Corps was not a part of the Navy and had never been. It was legally an independent branch of the military.

SECNAV offered a compromise. No more direct commissions for Marine officers. Starting with the Naval Academy class that began in 1877, all new Marine officers had to be Academy graduates.

In other times the Navy might have howled… but due to a political anomaly, the Navy was graduating far more quality graduates than it could commission. Budgets limited the number of new Navy officers… but politicos still wanted the patronage of appointing midshipmen. Some quality graduates were handed degrees and returned to civilian life.

The Navy officers thought that the plan was wonderful. Academy graduates would not be wasted… and the Marine Corps would gradually be taken over by “Navy” officers. Instead, the move helped save the Corps.

While proud of their time in the Academy, the officers did not think of themselves as “Navy”, but rather as Marines. The Navy had “tossed the Corps into the briar patch…”

In the decades to come, relations between the two services would improve to a large degree because officers from both branches serving together might well have known each other at the academy. While the Marine Corps would take some officers from other sources (due to increase in size) starting with the Spanish American War, a quality officer corps had been built.

The other big problem was that the Marine Corps was a service in search of a mission. Officers short of the Commandant himself selected by strict seniority… and a number of Commandant’s had limited vision.

Some could see no further than fighting to keep ship detachments. Others actively tried to tie the Corps to missions that would prove in later years to be dead ends. The closest that any of these came to happening was one Commandant offering to turn the entire Corps into “coast artillery…” This would have proved to have been a dead end, but fortunately the Army wanted the role for itself.

For a time Teddy Roosevelt ordered the Marines off the ships. Congress insisted that they be returned… and Roosevelt, who had more pressing matters went along with their demand.

Among the Navy officers pushing to get Marine detachments off the ships was a rather brilliant young man who felt that the Marines were being wasted. He felt that the Marine Corps should train ashore in battalion size units to be used as landing forces for the Navy.

During the Spanish American War the Navy wanted to set up a coaling station at Guantanamo. They asked the Army for troops. But the Army was “juggling bobcats” trying to train masses of volunteers and had nothing to hand for the Navy. Marines were scraped together from various ship and base detachments and took Guantanamo.

The young Navy visionary saw this as a sign. The Navy was spread over two oceans now… all the way to the Philippines and might someday need to seize islands and other locations for coaling stations. The Army might be busy, or just disinclined… but the Marines would be right to hand.

Unfortunately, the old Commandant’s couldn’t see it. Getting the ship detachments back satisfied them. When WWI arrived the big push was to get a Marine Division on the Western Front. Two Marine Brigades were sent, but only one saw combat… the other Pershing kept in “administrative” roles.

At the end of the war the Marines took stock. Realistically, in spite of a gallant record, the Marines were only a “tiny raft of sea-soldiers afloat in a sea of Army…” They had enough sense to know that being just “more Army” would endanger their existence. So they picked another mission… colonial infantry…

The Marines had fought in the Philippines putting down insurrectos. Into the early 20th Century they would intervene and occupy Haiti and other Latin American countries.

While the Army sometimes got involved, they much preferred that any troops outside the U.S. be in the Canal Zone or in the Philippines… The Marine Corps pretty much had a free run. Even during WWI, many Marines were in the Caribbean.

The Marines got very skilled at the colonial infantry role during the “Banana Wars…” Winston Churchill commented that they were one of the top forces in the world for that mission.

But FDR decreed that the U.S. was going to get out of the Banana War business. A new “Good Neighbor” policy would be substituted. The Marines were losing their primary mission.

The Marine Corps had an “Advanced Base” school with a small structure re occupying advanced bases for the Navy. But this was not enough… and the odds were increasing that “occupying” might prove very hard indeed.

For many years the Navy had been working on War Plan Orange… essentially a war with Japan. A brilliant Marine officer, Lt. Colonel “Pete” Ellis in 1921 “…wrote Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia a secret 30,000-word manifesto that proved inspirational to Marine strategists and highly prophetic…”

Ellis would later travel as a “civilian” to Micronesia to see for himself what the Japanese were doing to fortify the islands. He was almost certainly murdered… (See SOFREP article link re Ellis at end of this posting…)

In 1934 the Commandant decided that the Marine Corps was going to go all out for the amphibious warfare mission. But they would not even be starting at the beginning… amphibious warfare was already in a deep hole from the enormous bungle at Gallipoli on the Turkish European coast in WWI.

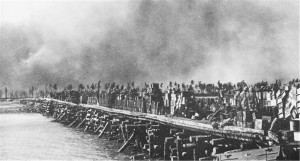

British, Australian and New Zealand forces landed on the Gallipoli peninsula in WWI with the idea of marching to Istanbul and opening the water route to the Black Sea and sending massive amounts of urgently needed weapons and supplies to Tsarist Russia.

Suffice it to say that everything that could be done wrong was… everything that could go wrong did. If you have seen the Mel Gibson film “Gallipoli” where the Australians have trenches dug part way up a cliff… with a beach not wide enough to toss a Frisbee… then you will have an idea. For many months… in heat and snow… running up obscene casualties to no purpose. At last evacuating the “beachhead…”

Every Western military staff was convinced by Gallipoli that amphibious assault against stiff defenses would be impossible. The Marine Corps studied Gallipoli carefully to see what not to do.

Even in the 1930s some Navy officers thought that “amphibious warfare” was nothing more than a few “whaleboats filled with bluejackets carrying rifles heading for a beach…”

The Commandant shut down the Marine Corps schools at Quantico and tasked all of the officers with coming up with a doctrine for amphibious warfare that would actually work. Everything from Naval gunfire, landing craft, air support, logistics. Not just infantry, but artillery, combat engineers… and countless other parts of the “machine.”

In January of 1935 the Corps produced what it called the “Tentative Landing Operations Manual.” With revisions, it would become not just the Marine Corps blueprint for amphibious operations… but would be adopted, word for word (with different titles) by the Navy and the Army.

In WW2 a number of Army Divisions (including my father’s, the 3rd Infantry Division) were trained in amphibious warfare by the Marines… and would later run their own training… More landings involving more troops were run by the Army during the war. But without the work in the 1930s there would have been no doctrine in place.

The Corps then went into the field to test the new doctrine. Revisions had to be made due to real world experiences. The Navy developed landing craft that were just awful. Too heavy, too slow, bad seaworthiness… and prone to sinking.

The Marine Corps ultimately went to civilian developers and came up with winners… modified and rolling off the production line in record time. Flat bottomed landing craft with ramps that dropped… and tracked vehicles that could move to the beach, cross over coral reefs if need be… and go some distance up the beach.

The real “graduation” was at Tarawa in 1943. One thousand Marines (and Navy Corpsmen) were killed in 72 hours at Tarawa… an island the size of Central Park. There were not enough tracked vehicles to make it over the coral reef… and the tide was lower than expected. Marines waded in from as much as 500 yards out under machine-gun fire.

A massive amount was learned. Naval gunfire was deployed in too flat a trajectory often landing in the ocean on the other side of the island. Aircraft going after bunkers needed to go in at a steep dive towards the front. Shelling had lifted too soon. And “beachmaster” arrangements had collapsed.

A beachmaster is a Navy officer… essentially a god who takes over once the first wave has moved off the beach. He is in absolute command of all logistics, traffic, casualty and prisoner evacuation and much else… all the way to the high water mark.

At Tarawa supplies were just dumped on the long pier in no particular order… to an insane height. Almost useless had the lads needed… and one hell of a target for an enemy air raid.

A number of months later the American Marines and the Army assaulted various islands in the Marshall’s group. Lessons learned on Tarawa were applied. Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT) made sure that the flat bottomed landing craft could make it all the way in.

Aircraft targeting was much improved… Naval gunfire not only continued on the beach until the last second… but the battleships got as close as they could without running aground. Casualties were very low. Amphibious warfare had come of age. Many (but not all) of the lessons would be applied at Normandy later in 1944. (Air and naval gunfire would largely overshoot the fortifications.)

At the end of WW2 the Army high command quickly lost interest in amphibious warfare. The Marine Corps went from six large divisions to two understrength ones.

The Air Force tried to declare that the other services were “obsolete” (except for a few soldiers to guard air bases.) The Navy lost interest in amphibious warfare… fighting to retain its carriers. The Army declared that amphibious warfare was obsolete because an enemy could just drop an A-Bomb on the fleet.

The Marine Corps went back to experimenting with new doctrine and equipment (including helicopter assaults from old WW2 carriers… though the implementation would not happen until after Korea). Meanwhile, the Truman administration worked to abolish the Corps.

Then on June 25, 1950 the North Koreans came boiling over the border… and MacArthur (who used to loathe the Marine Corps) demanded the 1st Marine Division for a master stroke at Inchon.

After Korea the Marine Corps got its WW2 carriers and had the Navy convert them into CVH (helicopter carriers holding Marine assault units…) At times the Marines found themselves dragooned into being “more Army” as in Korea after the Chosin Reservoir… in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. Their role in Gulf War One was mixed.

Many Americans without military experience (and unfortunately, some with it…) question why amphibious warfare is needed. “Can’t we just fly the troops where they need to go?”

Sure… if we don’t have to fly over any countries that refuse to let us use their airspace… If we won’t have to deal with any hostile aircraft. If there are proper facilities where we are going to disembark and refuel, and if need be repair. We had all of that in the early days of Gulf War One.

But infantry without heavy weapons and supplies is toast.

Even a C-5 could only carry one Abrams tank. A lot of troops need a lot of supplies and heavy weapons. Without them, well see Arnhem… (A Bridge Too Far…)

Saudi Arabia had giant bases, ports… and Saddam gave us months to move heavy equipment and supplies from port to port. It was nearly a commander’s dream.

Amphibious forces are deployed around the globe. They are able to put forces into any country that has a coastline… and they can supply them over bare beaches if need be. Our (more rational) potential enemies are fully aware of our capabilities to intervene from the sea. A Marine Expeditionary Unit can operate with as little as a battalion (fully supported) on up.

Sometimes a number of choppers from a newer amphibious ship might land at our embassy in, say, Kaffiristan and protect or evacuate the embassy and American (and often Allied) civilians. Shortly before Vietnam, Marines were deployed into the Dominican Republic and kept the lid on while the Army started moving in forces. And then there was Lebanon.

Article on Lebanon to follow shortly.

Y.P.

http://www.amazon.com/Soldiers-Sea-United-1775-1962-Stories/dp/1877853011

http://www.amazon.com/Marine-Search-Mission-1880-1898-Studies/dp/0700606084

http://sofrep.com/21900/pete-ellis-the-first-recon-marine/