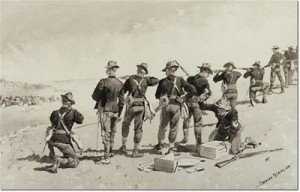

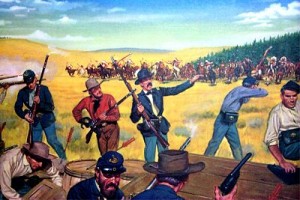

Protecting the wagon train by Frederic Remington

Protecting the wagon train by Frederic Remington Essay by Yankee Papa (all rights reserved)

In June of 1866 700 men of the 18th Infantry Regiment were marching out of Fort Laramie heading up the new “Bozeman Trail…” This would save hundreds of miles from the old route to the mines in Montana.

The weather was splendid and the troops were marching towards some of the most beautiful country in North America…at least in June. They were also marching into the hunting grounds of the Lakota, the Northern Cheyenne and the Arapaho.

That wasn’t supposed to be a problem. Peace Commissioners were meeting with the chiefs at Fort Laramie as they marched past. Unfortunately some of the chiefs were deeply opposed and nothing had been agreed upon when the troops showed up to build three forts in their territory. A couple of the most fierce, including Red Cloud called foul and rode off pledging war.

As they were too often wont to do, the commissioners decided to ignore the hostile or no show chiefs and just get the signatures of the ones present… even though it might not be their territory at issue. More than one war started this way.

But the word from the brass was that there would not be war… just some hotheaded chiefs… maybe some livestock raids on the posts. The high brass did not understand that as many as 4000 warriors might wish to dispute the matter with them.

The 18th had a proud record in the Civil War, but most of those lads had mustered out. Officers (who often had held higher rank during the war) and NCOs had seen combat… but not most of the common soldiers.

But… the brass indicated that there would be no major fighting. So many raw recruits and almost no training… just what little their NCOs could give them on their way. Drill and musketry not even scheduled until into the next year after the forts built.

The 18th was something new… it was not just made up largely of post-war men… but was among the first of the new blood on the frontier.

The remnants of the old marched past them as they neared Fort Laramie. The last of the “Galvanized Yankees”, former Confederates who volunteered to join the Union infantry to get out of the prison camps. Promised that they would fight Indians on the frontier, not their kin in the South.

Many were signed up for three years, and that meant that many were not discharged upon the end of the war. The last of the six regiments marched past the 18th on their way home to be discharged.

The soldiers of the 18th found that interesting, but were more concerned with their boots. Loss of weapons…illness and wounds… and bad feet could cripple an infantry unit.

Unless you paid a private boot maker, you bought “off the shelf…” In 1818 “lasts” were developed to enable production of specific left and right shoes… but this only came into common usage in the late 1850s… and with some minor exceptions, infantry in the Civil War and for some years thereafter (until Civil War stocks used up) had shoes with no left foot-right foot differentiation.

Prior to the march most NCOs would have shown the recruits how to fully soak the “boots” (up to the ankle and 4 sets of eyelets) and then let them dry on their feet before attempting to cover any distance in them. Easier to break in the boots than the feet.

Just as well that no fighting was expected…Colonel Carrington… well, everybody liked him, but he had never been in battle. Commissioned a Colonel from a law practice at the start of the war and handed the 18th Regiment… he was placed on “detached duty” for the entire war… staff duty in Washington.

If some of the officers thought that there might be a fight, they could not be happy at the Regiment’s strength… A new Civil War regiment contained 1000 men… the 18th only had 700… and of those all but 400 would be going to two forts… one at either end of the trail.

Actually they were lucky. A decade later and infantry companies on the frontier would not be at 70 like the 18th instead of the Civil War standard of 100… but down to a normal of 37.

And of course the rifles. The Ordnance Department had plenty of breech loading rifles in storage after the war… but chose to let the 18th head into the Powder River country with muzzle loading rifles (see https://gruntsandco.com/u-s-ordnance-rogue-fiefdom/ ) But then again, there was not supposed to be any fighting.

Only real Indian fighter around here, the Colonel’s guide… Jim Bridger. Even the recruits had heard stories about this old mountain man.

Bridger had his own assessment of what was going on. He thought that Red Cloud and some others would do more than just “steal some livestock…” A lot of horses, mules, and cattle that would have to be grazed outside the fort… Firewood to be cut some miles from the fort…something that required peace…

And then there were the women and children that the brass encouraged the Regiment to take with them. Total including workers of 400 civilians. Most would be at the fort in the middle of the trail… right in the heart of the Powder River hunting grounds. Colonel Carrington listened to Bridger… but the high brass assured Carrington that there would be no major hostilities…

[…The 18th had detachments build forts at both ends of the trail and built Fort Phil Kearny in the middle. Livestock indeed stolen and soldiers and woodcutters killed. On December 21, 1866, a Captain Fetterman… (had commanded the 18th at times during the war in higher brevet rank) put the seal on his disrespect to the Colonel and arrogantly disobeyed his orders.

Sent in relief of a wood chopping party, he instead rode after a party of Lakota to a ridge line. Ordered not to go past it, he did… with a mixed force of Infantry and Cavalry… 80 men. Just the number that he had boasted about… “With 80 men I can run roughshod over the whole Sioux nation.” Instead the Cavalry bolted to the front leaving the infantry panting behind… then more than 1000 Sioux rose up and caught them all in the open. It was over in a couple of minutes…

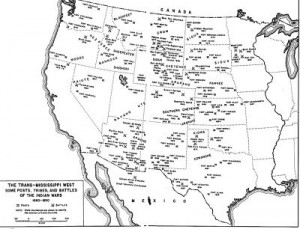

There would be other fights in the area, but the high brass in Washington decided what they should have in the first place… the soldiers could not guard the trail… only their own forts. Besides, Infantry needed to guard the trans-continental railroad that was being built. A treaty was signed… the troops pulled out by 1868 and the Sioux burned the forts behind them. It was the last war that Indians would win in North America…]

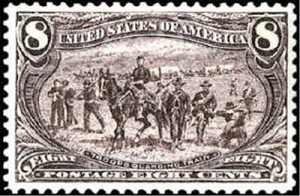

“Good Marksmanship and Guts” DA Poster 21-45

Near Fort Phil Kearney, Wyoming, 2 August 1867. The Wagon Box Fight is one of the great traditions of the Infantry in the West. A small force of 30 men on the 9th Infantry led by Brevet Major James Powell was suddenly attacked in the early morning hours by some 2,000 Sioux Indians. Choosing to stand and fight, these soldiers hastily erected a barricade of wagon boxes, and during the entire morning stood off charge after charge. The Sioux finally withdrew, leaving behind several hundred killed and wounded. The defending force suffered only three casualties. By their coolness, firmness and confidence these infantrymen showed what a few determined men can accomplish with good marksmanship and guts.

These days you mention the Old West and the Indian Fighting Army and people immediately picture Cavalry. Usually John Ford Cavalry. West had wide open spaces and the Indians had horses… so troops had to have horses… right? Oh, maybe some Infantry to guard the forts, but otherwise…

History tells a far different tale. There were never enough Cavalry… there never could be. The gigantic Union Army was mustered out and in the end, only 25,000 soldiers were left in the entire Army… many in the South enforcing Reconstruction.

A Cavalry regiment cost twice as much to raise as an Infantry regiment… and a lot more to keep running each year. And in spite of Hollywood… Infantry had a major role to play.

While mounted forces had played a role in every war from the Revolution on, there were no permanent regiments until the 1850s. Even then the mission a bit “fuzzy…”

Cavalry proper was supposed to fight almost exclusively on horseback. Dragoons were supposed to be able to fight some on horseback and some on foot. We had both, but at the start of the Civil War it was decided to call them all “Cavalry…”

Immediately after the Civil War a lot of regular and volunteer regiments were thrown into Kansas to put down Indian raids. Thousands of soldiers tracked endless miles and only killed two hostiles. Something else would have to be tried… and with a lot less soldiers… most of these were going to be demobilized.

Infantry would be needed for far more than to guard the forts. Wagon trains and supply trains would need escorts. While some Cavalry with the trains were handy… too many and they became a logistic nightmare.

American stock, unlike Indian ponies could not subsist on grass… Cavalry remounts needed oats and the like…a lot of them.

Even “all Cavalry” offensives had a limited range… In 1882 the assistant Quartermaster of the Army reported: “Unless cavalry operate in a country well supplied with forage, a large amount of wagon carriage must be furnished for forage and in such cases, cavalry is of little value except to guard its own train… and to do that in the presence of an enterprising enemy it will need the addition of infantry…”

Horses are, for all their size, relatively fragile. They can drop from a number of diseases and if worn out require an extended amount of time to recover. At the end of the day men are tougher than horses.

One officer who served in large expeditions in the Sioux and Nez Perce campaigns involving major units of Cavalry and Infantry, Sixth Infantry’s Col. William B. Hazen wrote “After the fourth day’s march of a mixed command, the horse does not march faster than does the foot soldier, and after the seventh day the foot soldier begins to out-march the horse, and from that time on the foot soldier has to end his march earlier and earlier each day to enable the cavalry to reach the camp the same day at all. Even with large grain allowances horses quickly deteriorated under extended exertion…”

In 1876 a 50 man Cavalry troop dismounted had less firepower on the line than an Infantry company of 37 men. Every fourth trooper had to take four horses to the rear and hold them there until the engagement was over. In addition the Cavalry was using shorter range carbines while the Infantry was using longer range (and more reliable) rifles.

The image of the “Cavalry riding to the rescue…” could not have been farther from the truth. In most cases, by the time that the Cavalry found out about a raid, the Indians could be fifty miles away… one hundred if they were Comanches.

Comanches might make a raid… then join up some miles off with couple of boys holding spare ponies… Alternate between them making distance. Cavalry, even an hour away would never catch up with them… just wear out their mounts. Cavalry had to dismount and walk their horses for a while every couple of hours to give them a breather. Meanwhile the Comanches kept swapping ponies.

One thing that cost the Cavalry was riding exhausted mounts into contact with Indians who were up for a fight… Reno almost lost his squadron when he had to retreat with blown horses (and exhausted, sleep-deprived troopers) at the Little Big Horn.

The only feasible military solution was to hit the hostiles in their villages… preferably in the winter when their mounts were scrawny. There were a number of problems with that strategy.

In the first place, during the Civil War a regiment of Colorado volunteers (enlisted for 100 days only) under a fanatic named Chivington had murdered many Southern Cheyennes at Sand Creek. Most of his men were bar sweepings and acted accordingly… rape, beheadings, “trophies” taken… slaves.

These Indians had followed the directive to camp by the nearest fort… but were ordered away by militia officers as a cynical prelude to slaughter. Other Indians were making the trouble… but these were closer… and both Chivington and the Governor of Colorado were looking for a cheap victory.

By the time that the people back East figured out what had happened, the regiment was paid off and the Army could do nothing. One regular officer who was going to testify was murdered in Denver.

So raids even into actual hostile Indian villages… though not as barbaric as Chivington’s would raise holy hell with people back East and their Congressmen.

And just what was a hostile village? Custer’s assault on Black Kettle’s village on the Washita, while not the insanity of Sand Creek was bad enough and raised troubling questions.

Black Kettle himself was an honorable chief who wanted peace. But war parties drifted in and out of his camp…some with hostages. He was not keen to have them rest up in his village… but tribal custom prevented him asking them to leave so long as they did not cause major trouble. He had no actual *authority*… as with most Plains chiefs, he led by his personality.

The Eastern media learned that Black Kettle had attempted to speak with the soldiers before the first shots were fired. He was shot and too many of the soldiers fired at anything that moved. It was a “victory” that would cost the Army in political support and in the unending enmity of both major branches of the Cheyenne people.

The biggest problem was identifying hostiles. Generally back when the Indian wars fought East of the Mississippi, a chief’s word would bind his tribe. On the Plains it was different.

A chief might sign a treaty with every intention of honoring it. But on the Plains both the war chiefs and the peace chiefs led by their personality and influence…not by compulsion.

Some members or clans of his tribe might decide to go their own way and raid. This caused reprisal raids (often by civilians) against the nearest members of that tribe regardless of any possible innocence. This of course led to those victims raiding the nearest whites… regardless of any possible innocence.

The reservation system was supposed to clear all this up. Those on the reservations would be labeled as “peaceful” and those off would be considered hostile.

But not all Plains Indians treaty bound to live on reservations. Some clans might…other might not. And some hostiles came to the reservations (mostly come winter) to rest up for new raids in the Spring. Some reservation occupants had permission to go off reservation on long hunting trips… Some were just that… others…

Shortly before the Little Big Horn campaign the government decided to reshuffle the deck. Indian tribes would no longer be treated as “sovereign nations” but as wards of the government. Certain tribes including the Sioux and Cheyenne were ordered (in winter) to report to a reservation or be considered hostile.

It is doubtful that many got the order…or would have considered moving in that weather… or even in the Spring. They saw no reason to give up their way of life.

The Army moved…and bungled the entire campaign…Custer’s blunders just one part of a bad set of events. But from this point the role of the Infantry would increase.

Like other troops on the frontier, the Infantry had some real problems. Their authorized strength too low… and usually could not meet that. Something like 37% of all troops on their first enlistment deserted each year.

Not just the low pay. Army preferred to pay in paper money at isolated posts. Counterfeiting so rampant for some years that most merchants would only take at a discount.

New troops got very little training. Most years no more than 16 rounds of ammunition per man for target practice. Often used on endless details having little to do with soldiering. If infantry present at a fort, they got most of the endless chores… most troopers work time centered around their mounts.

While officers preferred “Iowa farm boy” type recruits…they usually didn’t hang around. Many of the best soldiers were the Irish and Germans… at least those who made it into the NCO ranks.

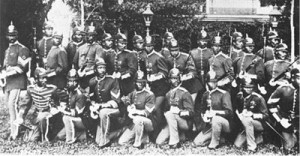

Many people have heard of the two regiments of black soldiers in the Cavalry. But there were also two regiments of Buffalo Soldier Infantry on the plains. On average they were a better investment than many of the white recruits.

Lot of drunks and loafers and other types likely to get into trouble and/or desert joined the white regiments… But there was a surplus of good quality men wanting to join the black regiments.

Desertion was a very small problem. Training took longer because of their background (this happened in Rhodesia with the Rhodesian African Rifles as well), but once trained up, these men proved superb soldiers.

Most white officers outside the black units looked down on the regiments…prejudice… nothing more. At the end of the Civil War Custer had refused the rank of full Colonel with a black regiment and chose to be a Lt. Colonel of a white one. (Actual commander, Colonel Sturgis always on temporary duty in Washington until after Custer’s death.)

Whether in garrison, or even in the field, the Buffalo Soldiers often looked smarter than their white counterparts. Some of that was their desire, and that of their officers to look like proper soldiers. Initially, part was because by the time that the black post-war regiments formed, the Army was out of their stocks of poorly made Civil War uniforms (bad contractors) and only had the later quality stuff left.

Company B of the 25th Infantry was stationed at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, from 1883-1888.

They pose here in their full dress uniforms. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo

After Custer’s famous luck ran out, the Army got orders to clean up the plains once and for all. The Infantry now would show what they could do.

The Infantry did whatever it took… The Fifth Infantry’s Colonel… Nelson Miles… put some of his troops on confiscated Indian ponies to help run the hostiles ragged and keep them from assembling in mass numbers.

But the real mission for the Infantry was a foot job… Hitting the Indian camps in the winter. The idea was not to win a big battle to the finish… Too often women (who often fought) and children caught up in the gun play and too many warriors would escape.

And a desperate fight for a village would often result in heavy casualties among the troops. At Big Hole later against the Nez Perce, troops from another Department would learn that the hard way.

The object was to cause the hostiles to flee… leaving their winter camps behind them… their shelter… massive food stores… and often most of their spare ponies. The best would be used and later sold… the rest shot.

The Indians would stagger into another village of the same or allied tribe… but they too could be hit by the “walks-a-heaps” tomorrow. One winter of the Infantry doing this broke the backs of the Sioux (many of whom fled to Canada…where only the Royal Navy prevented the U.S. Army from crossing after them…)and the Northern Cheyenne. The foot sloggers could hold up better in appalling weather than Cavalry remounts.

There were other campaigns on the plains… the Nez Perce battles that often involved Infantry… including their final one. Then in Northern California the Modocs in the lava beds where only the Infantry could operate. Others…

Against the Apache the Infantry had its work cut out for it. If Wyoming and Montana cold in the winter… the heat of the Southwest could be hell on earth. And the Apaches liked it just fine…

Other than the expedient of the Indian ponies, there were two primary ways that the Army could mount Infantry. European mounted infantry rode horses but always fought on foot and carried rifles… not carbines.

But it takes time to get Infantry used to the bone breaking gait of a Cavalry remount. Besides, especially in Apache country horses prone to dying even when cared for by specialists.

The answer was to mount the Infantry on mules. Mules can be stubborn…but once one accepts the rider, their easy walking gait far easier for a novice to handle. Add to that that other than camels (used for a time in the 1850s) they were the hardest critters to kill off in the desert. Unfortunately (from a Cavalryman’s standpoint) most mules will not charge into gunfire. Smarter than horses… and maybe their riders.

An elephant’s main strength is in pushing and pulling, but it can still handle a lot on its back. A properly packed Army mule could carry two thirds of the load (weight, not size) on its back that an elephant could.

One of the better Generals was a Colonel named George Crook who had worn stars in the Civil War and after dazzling victories in Idaho and Oregon was promoted to Brigadier General over a great many heads.

“Crook refined the science of organizing, equipping and operating mule trains … selection of mules civilian attendants preferred… proper design mounting and packing of pack saddles…” (Utley)

But the best partnership was Infantry on foot… with pack mules (no wagons that could not go into nasty country)and Apache scouts from the same tribe… day or two out in advance.

This partnership was put to the test in Mexico in the Geronimo campaign. After the Apaches surrendered, they said that this combination gave them the most trouble. They could always mount up and ride away from their hideouts… but American and Mexican Cavalry all over the place… sudden moves dangerous… Meanwhile the Infantry and mules would be maybe a day behind the scouts…as persistent as the scorching sun.

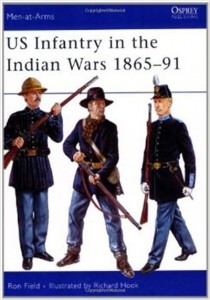

Grant’s troops in Virginia would not have recognized one of these companies. No bugles on the march…bayonets left in barracks. No glorious dark blue tunic over sky blue trousers.

Like Captain Henry Lawton’s company out of Fort Huachuca, they marched in white long underwear and campaign hats.

These companies marched without the drunks and the slackers. They had some of the roughest on the job training on the frontier…that produced hard-bitten professionals. They were a world away from the green 18th Infantry lads marching up the Bozeman Trail in 1866.

This period of the “Dark Ages” of the United States Army lasted from 1866-98. But these Infantry companies in Mexico would not have been out of place in many Twentieth Century campaigns… from the Philippines to Nicaragua…

-YP-

Suggested Reading

[CORRECTION UPDATE: The above version of YP’s essay is an updated version. The editor (me) originally published an earlier and slightly shorter version. Apologies to all.]